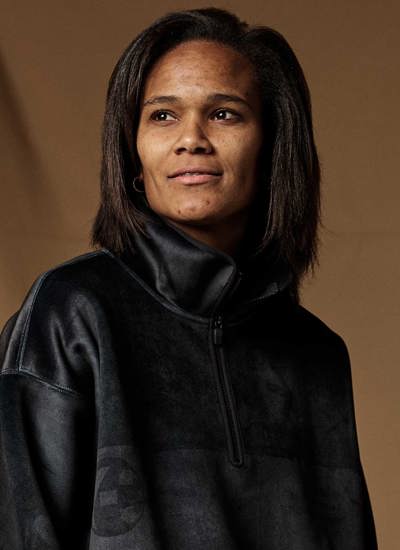

- Aldana Cometti celebrates with FIFPRO the improved conditions for players at Australia/New Zealand 2023

- "We’re being valued differently," says 27-year-old Argentina defender

- Cometti also discusses qualifying conditions and the need for a dedicated Women’s World Cup qualifying tournament in South America

Aldana Cometti has been representing Argentina at senior international level for the last nine years. The defender is about to play her second FIFA Women’s World Cup and never imagined that the scenario proposed for Australia/New Zealand 2023 would be so different from France 2019.

FIFA’s decision to substantially improve the conditions for footballers competing in the World Cup — thanks to the largest collective action ever taken in women’s football, with more than 150 international players from 25 countries co-signing a letter to FIFA president Gianni Infantino — was greeted with jubilation in the Argentina camp.

“For us South Americans, and the African girls probably feel the same as well, it’s a relief and it also means being able to help our families, who always help us and are always with us,” Cometti told FIFPRO, who conducted the negotiations with FIFA, celebrating an unusual level of financial income for the players.

Just for taking part in the championship, each player will receive at least $30,000, a figure that will rise to $270,000 for those who are crowned world champions.

“For us, any income – whether it’s $30,000, $15,000, $20,000 or $1,000 – is a load of money. It makes us very happy too because we’re being valued differently,” explains the centre-back, who at 27 is one of her country’s key players.

“This is like taking a weight off our shoulders for us and the people around us: ‘look what I’m achieving, look where I’m getting to, in the end everything I did as a little girl, as a child, going and training in the rain, on pitches that weren’t very good, with boys, has paid off’.

“We’re achieving something that maybe ten years ago, or five or three years ago, was unthinkable. When my family found out, they were proud of what we’d achieved as national teams, as players, as women, saying ‘girls, everything you did was worth it, because thanks to that you’re earning this money today’.”

Beyond the financial issue, the improvements in travel and subsistence conditions are very significant. Like the other delegations, Argentina travelled to the World Cup in business class, a huge difference compared to the past for a flight of around 18 hours.

“All these allowances for accommodation, travel, every aspect of preparation, have enabled us to stop worrying about having to make a journey lasting so many hours. Or being in the same base camp. Not carrying all your stuff from one place to another, thinking about whether you haven’t got this or that. That didn’t work well in the last World Cup. Now our minds are going to be a hundred per cent focused on the matches and training.”

In Cometti’s view, this achievement confirms the power of collective action: “When we get together, when we all have a common objective and move forward, whatever the country, whatever the national team, we achieve great things.”

Cometti knows perfectly well what fighting for better working conditions means. In 2017, after two years of inactivity as a team, the Argentina women’s national side went on strike to demand basic resources from the Argentine Football Association to return to training.

Since then, and after winning their first point in a World Cup in 2019 by drawing with Scotland, Argentina has gradually improved its preparation conditions.

“We’ve had four years of friendlies and training camps, plus the Copa America. The number of matches before this World Cup is millions [sic] compared to what we had for the previous one. We’re arriving much better prepared.”

2023 FIFA Women's World Cup: Fragmented calendar and lack of data holding back international progress in women's game

Despite the positive strides made, the gaps when compared to other World Cup teams are still evident. As FIFPRO published in its recent 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup Workload Journey Report, Argentina played 35 matches up to 23 May this year: 11 in official competitions and 24 friendlies. Sweden, its World Cup Group G rival, played 48, 27 of them official.

This unevenness brings into focus FIFPRO’s call for a single qualifying process that will give women’s players more opportunities to play and reach their full potential. South America uses its Copa America as a qualification route not only for the World Cup but also for the Olympic Games.

“I would change the qualifying system. Currently, a tournament that is played every four years qualifies you for everything. And your future for the next four years depends on it! You play for two weeks with your life at stake. We only have two days to recover between matches and it’s not ideal for high performance. And there are many teams, such as Bolivia and Peru, that don’t arrive well prepared because they hardly have any friendlies,” Cometti reflects.

“It would be more productive for South American football to have 18 qualifying matches, as the men do. Or to separate us into two groups and have 10 matches. And to play the Copa America separately, so that it’s not a qualifier but it is an achievement to win it. It’s a different approach.”