Our guests’ opinions do not necessarily reflect the position of FIFPRO

We are living through a time of unprecedented growth in women’s football. In 2019, more than one billion people watched the FIFA Women's World Cup; next year’s tournament is set to do even better.

The expansion of the World Cup to 32 teams, from next year, offers one of the most visible and significant measures of the industry’s growth. While the men took 44 years to grow from a 16-team competition to its current size, it has taken the women just over half this time.

Expanding competitions for the sake of it, however, can be detrimental to the game. The uneven and varying levels of investment in women’s football have historically undermined competitive balance, creating poor experiences for players and fans.

Expansion goes to the heart of the international calendar and whether it can bring stability to the women’s industry, find a healthy balance between club and country, and ultimately enable players to develop as athletes and reach their full potential.

Thankfully, statistical modelling provides some of the answers – it helps us to understand and predict both the quality and the degree of uncertainty, or jeopardy, of sporting competitions. It gives stakeholders an increasingly powerful tool as they seek to optimise outcomes for individual tournaments and the international calendar as a whole.

Our forecasting system that ranks national teams allows us to understand how the World Cup’s expansion to 32 teams might affect competitive balance across the tournament.

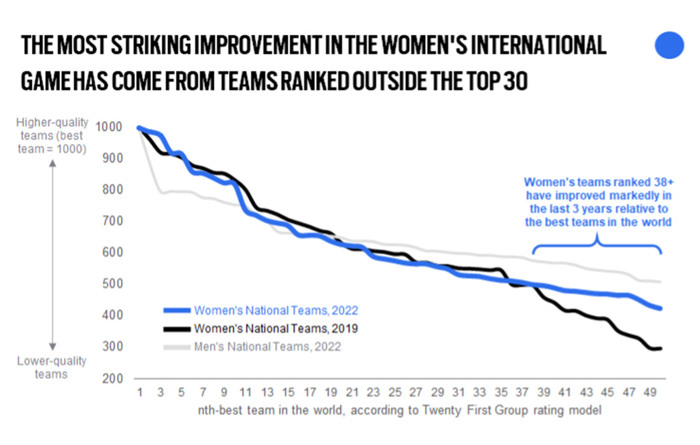

What does expansion mean for the relationship between the strongest and weakest teams, and how does this affect the competition as a whole? Interestingly, as this diagram shows, it is the teams outside the top 32 who have improved the most over the last three years – and not those ranked from 25 to 32.

In theory, we might worry that the eight additional teams in the 2023 World Cup could reduce competitive balance, by bringing in a number of weaker teams. However, there is no reason why a 32-team World Cup should correspond perfectly to the global ranking of national teams.

The 2019 tournament featured Jamaica, for instance, who were ranked 40th in our model that year. Looking to 2023, two teams from outside our top 40 have already qualified for the finals.

Our simulations for next year, based on our modelling of the most probable qualifying teams, predict an average of 3.3 group-stage matches with a goal difference of five or more – a negligible increase on the 2019 average of two games. (The 2019 tournament also included 12 fewer group matches in total.)

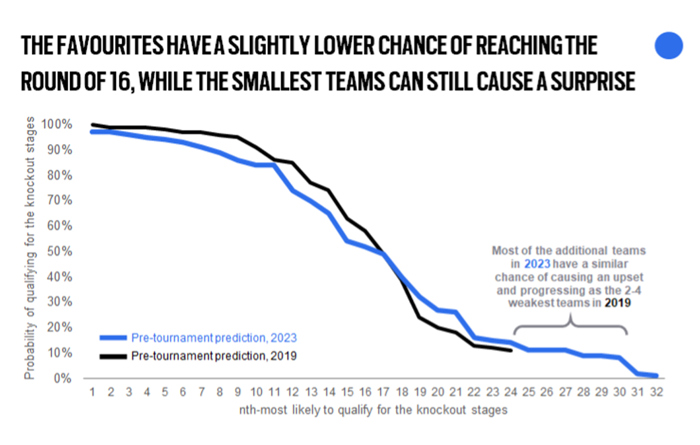

Jeopardy matters not only for the outcome of each individual match, but also for the tournament as a whole: players relish the tension of competition. In 2023, the smaller percentage of teams qualifying from the groups may produce more surprises: there is more chance that the favourites go home early.

Moreover, the strengthening of some of the weaker teams in the tournament means that many of the pot-four teams in each group still have a chance of causing an upset and progressing, as Nigeria and Cameroon did in 2019. This means more competition and more excitement for everyone.

Our modelling also suggests that 47% of the final round of group games will be a ‘dead rubber' – with no sporting outcome at stake – for at least one of the teams involved. This would be almost identical to the 50% we saw in 2019.

While no World Cup match is ‘meaningless’, players from some teams will enjoy the same opportunity, in the final group game, to rest and recuperate ahead of the knockout stages.

The quality of matches and the uncertainty of their outcome are fundamental to how we perceive a tournament and its main actors, the players. Even before a ball is kicked, we can predict with confidence that the 2023 World Cup will continue to promote women’s football as world-class sport and entertainment.

As the women’s football industry continues its rapid growth, some might be tempted to replicate the structures of the men’s game, even as it faces formidable challenges. This is why evidence and analysis are so vital: they offer alternatives.

By using data to forecast competitions, we can encourage all the stakeholders to sit down and work together on new solutions. It opens up the prospect that the people working at the heart of the industry – the players – can develop their careers as top athletes, supported by an international calendar that brings stability and fair competition.

Do it well and, as with next year’s World Cup, everyone stands a chance of winning.

About

Omar Chaudhuri

As Chief Intelligence Officer of the sports intelligence agency Twenty First Group, Omar Chaudhuri supports sporting organisations in strategic decision-making and storytelling using the power of data. Over the last ten years he has worked alongside football clubs, competition organisers, and investment groups at the highest levels of the game, helping them understand how effective use of analytics can deliver sporting success and unlock commercial value.